Valdelsa Valdicecina

When millennia-old beauty and rolling hills go hand-in-hand

The landscape in the Val d’Elsa and the Val di Cecina are begging to be captured on film, as if it were the only way to absorb its beauty. Even the towns want to be sung about, immortalized at every hour of the day, painted, as if their splendour need be treasured, their limitless wonders contained so they won’t be wasted, so they can be conserved for future generations, just as we’ve received them from times gone by.

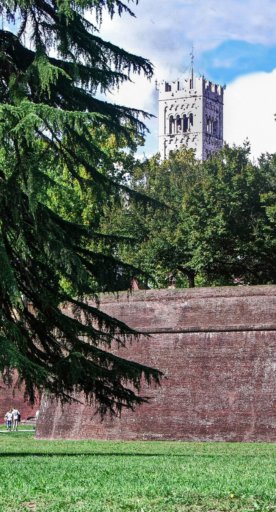

It was the Etruscans who understood that these hills, so unassailable and isolated, could be an envious oasis, a safe place far from the known-world where they could develop their civilization. Since their time here, the oft-mysterious atmosphere pervading these small and large villages remains unchanged. The charm of vaunting ancient roots still remains strong, seen in people’s names, in the way they speak and in everyday activities. And none of this takes away from the enchanting influence of the Middle Ages, when the streets in these villages were paved, gates were built, traditions were instilled and walls were built that today leave no one out, but rather, simply, safeguard what’s within.

There are two continuous valleys that are centred around Volterra, which watches from above without cutting into their space and individuality. There’s the Val d’Elsa, marked by the via Francigena, which, like the river that’s shaped the land’s topography, has moulded the surroundings, the villages and the character. Casole and Radicondoli, for example, still preserve a sense of rurality. They have defense walls and chiassi, Roman villas and country homes, and they certainly have a sort of interior metronome, that is, the rhythm of tradition. In the Val d’Elsa, history is a living book and some of its pages can be undoubtedly read in San Gimignano, a UNESCO World Heritage Site known as the “Manhattan of the Middle Ages” thanks to its intact medieval towers. Towers like these can also be seen in Monteriggioni, beloved even by Dante Alighieri. Other pages speak of Colle Val d’Elsa, home to a tradition of crystal-making and the birthplace of Arnolfo di Cambio. Then there’s nearby Poggibonsi, which despite its clear modernity, is as old as the entire valley.

Volterra, or Velathri, the Etruscan name, sits atop a hill (like its inhabitants will tell you); while its strategic position for spotting approaching enemies is no longer important, today’s visitors can enjoy an incredible view that stretches nearly 40 kilometres. Fragile, but also flexible and dynamic like its famous alabaster, the town’s cultural vivacity has never waned, from the Etruscan era to today. Just look at the Val di Cecina, which extends from the coast to the highest hills, where the nature reserves of Berignone, Montenero and Monterufoli give way to a land that can hardly contain its energy, emerging form the fumaroles of Sasso Pisano, the hot springs and the geothermal field in Larderello.

When nature’s elements are harmonized, when a balance between air, land, water and fire is maintained, that’s how a land like this one comes to be.